Obtaining hydrogen from water is one of those topics that attracts lots of attention from many fronts in chemistry; on paper, it can be clean, elegant, and deceptively simple. In practice, however, water is stubborn and breaking it apart requires catalysts, large energy inputs, or clever chemistry that juggles thermodynamics and kinetics.

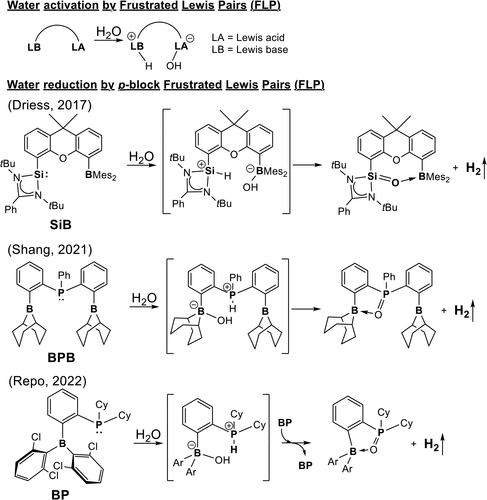

Among the many clever ideas proposed over the last decade, frustrated Lewis pairs (FLPs) stand out. They famously activate H₂ without metals, they’ve been pushed into CO₂ chemistry, and more recently they’ve been suggested as candidates for water reduction. Some experimental reports even hint that certain B–P FLPs might pull it off.

But the research of our colleague Dr. Rong Shang (then at the University of Hiroshima, Japan) poses an uncomfortable question: Do these systems really reduce water — or are we projecting wishful thinking onto favorable-looking reaction schemes?

This is not a semantic question. It’s a mechanistic one. And it’s exactly here where my colleague and good friend Dr. J. Oscar Jimenez-Halla (University of Guanajuato) got involved with his computational chemistry insight and kindly enough called me onboard this fascinating quest.

Why water reduction by FLPs is not obvious at all

On paper, an FLP looks perfect for the job. You have a strong Lewis acid (boron), a strong Lewis base (phosphorus), and enough steric bulk to prevent them from forming a (dative) bond. Put them near a small molecule and interesting things happen when they pull from a covalent bond within. However the case of water is different from that of H₂. It’s polar, hydrogen-bonded, and thermodynamically stable in ways that make simple activation a misleading phrase. Any claim that an FLP reduces water must survive three brutal questions:

- Can the FLP bind water in a chemically meaningful way?

- Can it cleave the O–H bond without falling apart?

- Can the overall process compete energetically with decomposition, quenching, or back-reaction?

Rather than answering these questions for a single hand-picked system, we decided to do something less flashy and more revealing: a comparative, systematic theoretical study of multiple B–P FLPs under the same computational lens.

We examined a family of B–P based frustrated Lewis pairs with varying electronic and steric features, using consistent DFT protocols to map out the full reaction landscape for water reduction. Not just “does a transition state exist?”, but how high is it, what stabilizes it, and what competes with it.

This matters because isolated mechanistic snapshots are dangerous. You can almost always find a transition state if you look hard enough. What matters is whether the pathway is chemically viable.

(Insert Figure 2: Reaction energy profiles)

The uncomfortable result: not all FLPs are created equal. Most B–P FLPs are bad at reducing water.

Some bind water weakly. Others activate it but get stuck in deep thermodynamic wells. A few manage to cleave an O–H bond, but at energy costs that make the process irrelevant under realistic conditions.

What makes this particularly interesting is that many of these systems look promising if you only examine frontier orbitals or isolated steps. It’s only when you trace the entire reaction coordinate that the problems become obvious.

In several cases, the bottleneck isn’t even the O–H cleavage. It’s the reorganization energy, the loss of frustration, or the stabilization of unproductive adducts. In other words: the chemistry fails not because FLPs are weak, but because they’re too good at doing the wrong thing.

Water reduction by FLPs is indeed possible, and this is where the story gets interesting.

A subset of B–P FLPs does show comparatively favorable energetics. Subtle tuning of Lewis acidity, basicity, and steric confinement reshapes the reaction landscape in ways that dramatically lower barriers and destabilize dead-end intermediates.

I guess the overall takeaway message is that this work is not just about water reduction. It’s about how we evaluate bold mechanistic claims. We need to stop just validating ideas and start stress-testing them. Our study shows how easy it is to over-interpret isolated favorable features and how powerful it is to systematically compare related systems under a given (tested) theoretical framework.

Frustrated Lewis pairs are extremely sensitive to electronic tuning which makes them perfect testbeds for computational chemistry done right. Water reduction by FLPs is not a solved problem. Not even close. But for progress to happen, we need more of this careful, comparative, and occasionally disappointing analysis.

You can read the whole paper at ACS Inorganic Chemistry DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.5c04108. As before, thanks to Prof. Oscar Jimenez-Halla for inviting me and to Leonardo “Leo” Lugo for his hard work.